Reposting another article by Philip published in BusinessWorld on February 14, 2018.

How governments can screw up the development of new drugs

by Philip Stevens

THE PATENT-BASED system of drug development will come under further pressure from key countries aiming to increase access to medicines at the executive board meeting World Health Organization in March.

Critics of the system want reform, arguing it makes drugs too expensive and fails to provide cures for those in need who may be unable to pay, such as people in developing countries. They want to slash drug prices by replacing intellectual property rights with government-funded prizes as the primary innovation incentive for medicines.

Developers of new drugs would gain government cash prize rewards for the successful development of a new medicine.

In return, companies would be forced to hand over their intellectual property rights to the government, allowing generic manufacturers to enter the market immediately. Competition between generic drug manufacturers would boost access to those in need as new drugs would be sold at their marginal cost of manufacture, so the theory goes.

Meanwhile, governments would control and plan what disease areas are rewarded by prizes, ensuring that funding is allocated to health priorities in a fair and transparent fashion.

“Delinking” the cost of R&D from the final price paid for a medicine, and making governments the funders and planners of drug development, sounds like a simple public health care solution. But so far, no country has taken the plunge.

This is not surprising; “delinkage” is not the silver bullet claimed by its supporters.

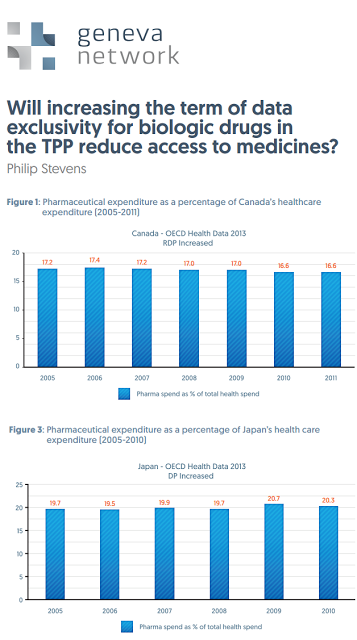

One charge leveled against the patent-based system is that it creates losses for patients by inflating medicine prices well beyond their manufacturing costs. This downplays the economic benefits of new medical technologies from averted hospitalization and fewer sick days for workers. But more to the point, an innovation system based on prizes could create just as many, if not more, economic losses.

The prizes fund would have to come from taxpayers; their burden would be at least the $141 billion spent by the private sector on R&D each year. Income tax hikes would distort labor markets and interfere with job creation.

Then there would be the added costs of the enormous new bureaucracy to manage the prizes system.

In the absence of private sector investment, which country would be willing to fill this funding gap? Here the rhetoric of many countries, including India, at World Health Organization meetings in Geneva has not been matched by serious action. Even modest WHO R&D delinkage “demonstration projects” fall $73 million short of the $85 million required, with contributions from only 10 countries.

This new world of government-funded prizes to drive medicine innovation does not look promising.

Money apart, designing prizes that work is even more of a problem. Government committees would struggle to determine the true economic and social value of medicine before it is even created.

With estimates for developing a new medicine between $1.2 billion and $2.6 billion, this matters a whole lot.

For prizes lower than the true market value of the invention, drug developers — and the venture capitalists so instrumental for start-ups — would direct their capital away from medicine R&D towards politically safer but less socially useful areas. New medicines would dry up.

For prizes lower than the true market value of the invention, drug developers — and the venture capitalists so instrumental for start-ups — would direct their capital away from medicine R&D towards politically safer but less socially useful areas. New medicines would dry up.

If a government prize committee overvalues the prize, it would trigger duplication of R&D as competitors swarm. Curious then that proponents of these prizes argue they will end the supposedly “wasteful” and duplicative R&D under the patent system.

Finally, there is the problem of politicization. A prize system would hand significant new discretionary powers to government officials as the judges of which medicines win prizes. Political factors would influence decisions on where to allocate funding, rather than clinical need. Diseases that could summon the most vocal lobby groups would get attention from prize bureaucrats, while less fashionable diseases may be ignored.

Political connections and lobbying could both play a role in securing a prize, while elected officials may attempt to influence R&D spending by government agencies.

Patents, on the other hand, represent a far less arbitrary form of innovation incentive. Government merely sets the framework of patent law, under which all companies compete. And competition is the key to innovation.

Take hepatitis C, until recently an incurable disease afflicting around 12 million Indians. Since 2013, no fewer than 10 new treatments have come onto the market, offering clinicians a huge range of options. Such breadth and speed of innovation under a winner-takes-all prize system is hard to picture.

Despite their superficial attraction, no country (other than the technologically backward former Soviet Union) has yet replaced intellectual property rights with prizes. The reasons are clear. Prizes risk economic distortions, undermining incentives for innovators, and adding a new layer of bureaucratization and politics. Be warned, therefore: delinkage and drug development do not go hand in hand.

Philip Stevens is director of Geneva Network, a UK-based research organization focusing on trade, innovation and health policy.